Seyyed Hossein Nasr on Role of Thinking in Islam: Past, Present, and Future

EDITORS’ NOTE: Seyyed Hossein Nasr — a prominent Islamic philosopher and one of the most important scholars of Islamic, Religious and Comparative Studies — discusses his insights on Islam and the modern world, his criticism of, and solutions to, Western approaches to religious education, the importance of traditionalism, the role of thinking in Islam, and his own personal search. This interview was published for the Boniuk Institute of Rice University.

Short Excerpts from the Interview

The History of Teaching Religion in Western Universities

Sahil Badruddin: In your 2014 lecture at the Ismaili Center Burnaby, you mentioned that the study of religion itself has become secularized. Specifically, you said: “What is happening now in American and Canadian universities is that you teach religion under the condition that you do not believe in it. It is like teaching music under the condition of being tone deaf. That is only done for the field of religion and not any other field.”

Dr. Seyyed Hossein Nasr: That is right.

SB: Why is this happening and then what changes would you recommend?

SHN: Why this is happening is very clear. The Western universities (with the exception of some Christian universities) became gradually the hotbed of secularism, except for usually the divinity schools that trained ministers and priests and so forth. …

In earlier days, the study of religion revolved especially around Western religions, and religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism or Islam were considered to be cogent only if they were studied as “objective” historical facts and not as truths or living faiths. Already in the 19th century in Germany there developed what was called the science of religion or Religionswissenschaft. Then it spread to England and France and later on to the United States.

The idea was to develop a new discipline that would study religion “objectively” as if one were studying, let us say, botany. It is on the basis of that fact that I made that criticism. This outlook became a condition for studying religion in most places for religion departments in the United States, when they began to grow after the Second World War. One was expected to teach religion provided one did not believe in it. As for the phenomenological study of religion, which also began to grow, it was also not interested in the ultimate meaning of religious truth. Believing involves one’s existential participation and it was thought that such a reality would make the study of religion subjective and not acceptable in a university setting. As I have said, this is the most absurd thing in the world!

The idea was to develop a new discipline that would study religion “objectively” as if one were studying, let us say, botany. It is on the basis of that fact that I made that criticism. … One was expected to teach religion provided one did not believe in it. … Believing involves one’s existential participation and it was thought that such a reality would make the study of religion subjective and not acceptable in a university setting. As I have said, this is the most absurd thing in the world!

SB: [Laughs]

SHN: [Laughs] You would never, as I have said jokingly, create a department of music under the condition of having only professors of music who would be tone deaf. They will be able to read a score and so forth, but they would not appreciate the music, for if they did, that would make their teachings subjective. To know but also appreciate Bach, Beethoven or Brahms would make their courses subjective. As I said, this is really absurd. Even in the physics department — I studied physics at MIT — the professors had a love for the discipline. They looked at it purely objectively in the laboratory, but the worldview of most of them was determined by physics and they had a very strong personal attachment to that worldview. They saw the world through the eyes of physics. That means that they were attached to it. Of course, science claims to be purely objective, but that claim itself is philosophically false.

Even in the physics department — I studied physics at MIT — the professors had a love for the discipline. They looked at it purely objectively in the laboratory, but the worldview of most of them was determined by physics and they had a very strong personal attachment to that worldview. They saw the world through the eyes of physics. That means that they were attached to it. Of course, science claims to be purely objective, but that claim itself is philosophically false.

Nasr: “The Great Honor of Not Thinking” and Increasing Anti-Intellectualism Amongst Muslims

SB: We often talk about the intellectual tradition of Islam. You have said in a lecture on Islam and the modern world that “there has been an increasing trend among Muslims of anti-intellectualism, the great honor of not thinking.”

SHN: That is right.

SB: You said, “In Islam, it occurred very recently, and it went against the grain of the whole of Islamic civilization that always emphasized ‘ilm, knowledge, knowing, learning, etc.”

Can you elaborate on what you mean by “the great honor of not thinking”? …

SHN: … What I mean is that there re-developed in the Islamic world an element of that opposition to thinking about and meditating upon matters of religion, as there was also in other religions where there appeared schools of thought that said that you should only follow what “the gods” have said and not “think” about it. And so, we also observe such a phenomenon in Islam, but before modern times it was always a minority voice. The majority of schools in Islam, both Sunni and Shi’ite, always emphasized the importance of thinking, of intellection, of knowledge, following the teachings of the Quran and Ḥadīth on this issue.

The Quran equates actually being saved, being attached to God, with using our ‘aql. People who do not understand the reality of religion are not using their intellect. They do not think correctly and therefore do not understand. The Quran is based on the primacy of knowledge combined with faith, the highest of which is Lā ilāha illa’Llāh (There is no god but God), from which flow other forms of authentic knowledge. …

The Quran equates actually being saved, being attached to God, with using our ‘aql. People who do not understand the reality of religion are not using their intellect. They do not think correctly and therefore do not understand. … The main challenge today that the Islamic world faces is not American bombs or anything like that. It is ideas. It is ideas that are challenging the whole existence of Islam, and so our main challenge is intellectual, and it cannot be answered by anti-intellectualism.

The main challenge today that the Islamic world faces is not American bombs or anything like that. It is ideas. It is ideas that are challenging the whole existence of Islam, and so our main challenge is intellectual, and it cannot be answered by anti-intellectualism. On the one hand, there is the preservation of religion while confronting the West, although of course that has also weakened in certain circles. On the other hand, there is the anti-intellectualism that leaves the whole back door open. …

SB: In that same vein, it would seem to me that without new thought, new perspectives, new ideas, all we are really left with is existing past knowledge, which eventually degenerates into an unchallengeable prescriptive corpus of dogmatic orthodoxy. What can be done to reverse or diminish these unhealthy trends?

SHN: First of all, I do not agree with you about the negative use of the term dogmatic orthodoxy. I know what you mean, but that is also itself a prejudice of modernism. Dogma, originally a medieval Christian term, meant actually authentic belief about God and other religious doctrines, which were based on truth. And orthodoxy means ultimately Sirat-al-mustaqim, the right path, and also the right doctrine (ortho-docta). I consider myself to be completely orthodox, but I do not consider myself to be dogmatic, in a sense of trying to force my ideas upon people.

SB: Which is what I meant, right.

SHN: In addition to faith, I can provide arguments for my beliefs, and I am adamant in preserving my worldview because I have studied it and gained certainty about its truth through both faith and intellection. I have written about it; I have taught about it for decades on the basis of the certainty of the truth that it contains.

SB: Of course.

Representing Traditional Islam in Contemporary Language for Today’s Minds

SHN: Living religion is actually like a spring; water continues to flow from it, which then inundates and nourishes the fields around it. It does not have to change, but what it does have to do is to remain a spring, to remain active. What Islam is today, what modern is, what reformism is, are defined often by people who have mostly weak intellectual knowledge of the Islamic tradition. In twenty years’ time, who will read what they are writing now? I am sure that you have seen examples of famous reformists who were writing in Pakistan or some other Islamic country thirty years ago, but who have now faded into obscurity and no one hears about them anymore.

Living religion is actually like a spring; water continues to flow from it, which then inundates and nourishes the fields around it. It does not have to change, but what it does have to do is to remain a spring, to remain active. … What is important is to represent traditional Islam in a contemporary language, to write about the eternal truths in a contemporary language.

What is important is to represent traditional Islam in a contemporary language, to write about the eternal truths in a contemporary language.

SB: Yes, I agree.

SHN: In the field of mathematics, nobody says that since two plus two equaled four at the time of Pythagoras, it is now old-fashioned and out of date.

SB: [Laughs.]

SHN: [Laughs.] We do not say that we are now in the 21st century; so let’s put aside these old ideas. But that is what is said often about religion. Lā ilāha illa’Llāh (There is no god but God) is in a sense for us Muslims like two plus two equals four, but it needs ever fresh interpretations for every generation.

In the field of mathematics, nobody says that since two plus two equaled four at the time of Pythagoras, it is now old-fashioned and out of date. … [Laughs.] We do not say that we are now in the 21st century; so let’s put aside these old ideas. But that is what is said often about religion. Lā ilāha illa’Llāh (There is no god but God) is in a sense for us Muslims like two plus two equals four, but it needs ever fresh interpretations for every generation.

SB: Good point, yes.

SHN: We Muslims have to accept our share of blame for the difficult situation in the Islamic world today. We have to accept our own faults, and cannot only blame the West, although of course the West has played an important role in the creation of our present state. Part of our intelligentsia became disinterested in Islamic thought and culture and went to study Western thought, Western ideas, and so forth. Such people became third-rate Western intellectuals with Muslim names. The other part of our intelligentsia was the traditional intelligentsia, which did not realize the challenge of the modern world and did not respond to it as it should have from the 19th century onward. Members of the traditional intelligentsia went into their cocoons with a few exceptions here and there.

A few people became moderate modernists or fundamentalists in between who did not have the intellectual power to be able to re-establish the central norms of Islam. Some of them were stronger and some of them were weaker, but none of them could really do the job. So, we are in a situation in which we have to be able to be rooted deeply in the Islamic tradition and at the same time to be contemporary. Traditional and contemporary are not contradictory as some people think.

SB: Agreed.

SHN: I consider myself a traditional Muslim, but I am also contemporary. This is possible, and I hope, inshā’a’Llāh, that the younger generation of Muslims who are coming up, especially many who live in the West and know the West well, will not be fooled by superficial things coming from the modern West as many of our youth are in the Islamic world itself. And I hope that they will come to study matters more deeply and be able to present Islam in its authentic traditional aspect but in a contemporary way. A tree whose falling autumn leaves reveal bare branches and has an appearance of death will become full of green leaves once again in the spring. The tree may appear to be new, but it is the same tree with new shoots. The tree preserves its nature while going through seasonal cycles; it continues its identity; it bears fruit, the same fruit as in earlier seasons, but this is a new phase in its life.

We Muslims have to accept our share of blame for the difficult situation in the Islamic world today. We have to accept our own faults, and cannot only blame the West, although of course the West has played an important role in the creation of our present state. Part of our intelligentsia became disinterested in Islamic thought and culture and went to study Western thought, Western ideas, and so forth. Such people became third-rate Western intellectuals with Muslim names.

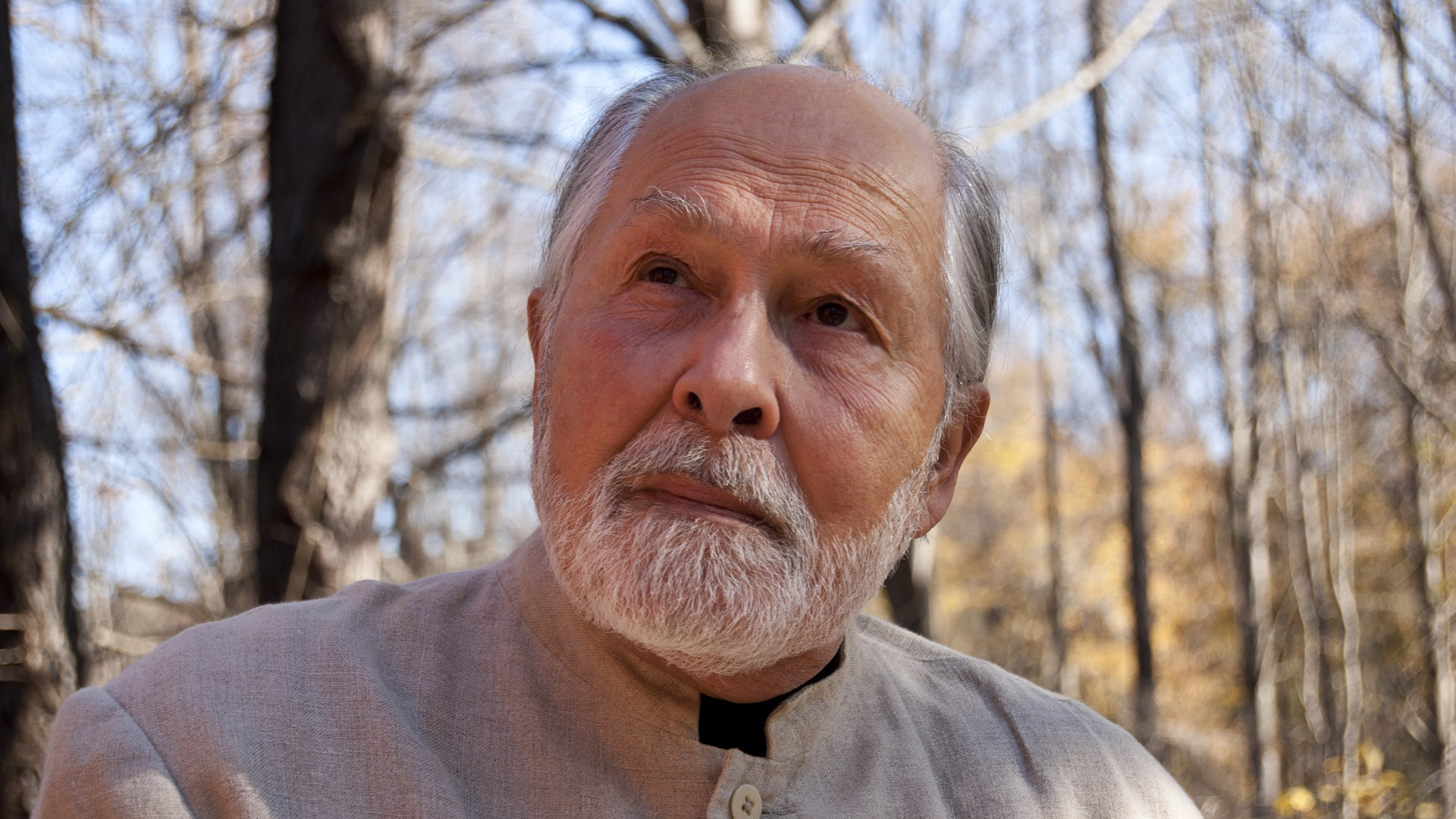

ABOUT SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR

Dr. Seyyed Hossein Nasr, currently University Professor of Islamic Studies at the George Washington University, Washington D.C. is one of the foremost scholars of Islamic, Religious and Comparative Studies in the world today. Author of over fifty books and five hundred articles, which have been translated into several major Islamic, European and Asian languages, Prof. Nasr is a well-known and highly respected intellectual figure both in the West and the Islamic world. An eloquent speaker Prof. Nasr is a much sought-after speaker in his area of expertise. Possessor of an impressive academic and intellectual record, his career as a teacher and scholar spans over many decades.

He writes and speaks on topics such as Traditionalist metaphysics, Islamic science, Religion and the Natural Environment, Sufism, Spirituality, Music, Art, Architecture, Science, Literature, Civilizational Dialogues and Islamic Philosophy, and has been described as a ‘polymath.’